390 years ago, in London’s Devil’s Tavern, a small group of poets and writers founded a literary circle that was destined to become the first English club. In the centuries that followed, gentlemen’s clubs became as recognizable as cricket and fox hunting in the English way of life, and were emulated in many countries. However, no one managed to reproduce the British original.

In the distant 17th century, all states were divided into two categories: those in which there was a strong despotic power of the sovereign, and those where complete anarchy reigned. The only exception was England, where power and society were equally strong and knew how to get along more or less peacefully with each other.

The secret of the power of English civil society lay not only in the wealth of the London merchants or in the authority of the noble landlords. The fact was that the British were the first to learn to communicate outside the framework of official institutions – they invented clubs, interest societies in which people could discuss any issues related to both personal and state affairs in a pleasant atmosphere, thereby shaping public opinion.

Which even ministers and kings had to reckon with. They tried to imitate the English in other countries but they could not reproduce the spirit of the English club anywhere, because in no country was there what the community of English gentlemen rested on – specific British humor, without which any club became only a parody of Albion.

School of slander

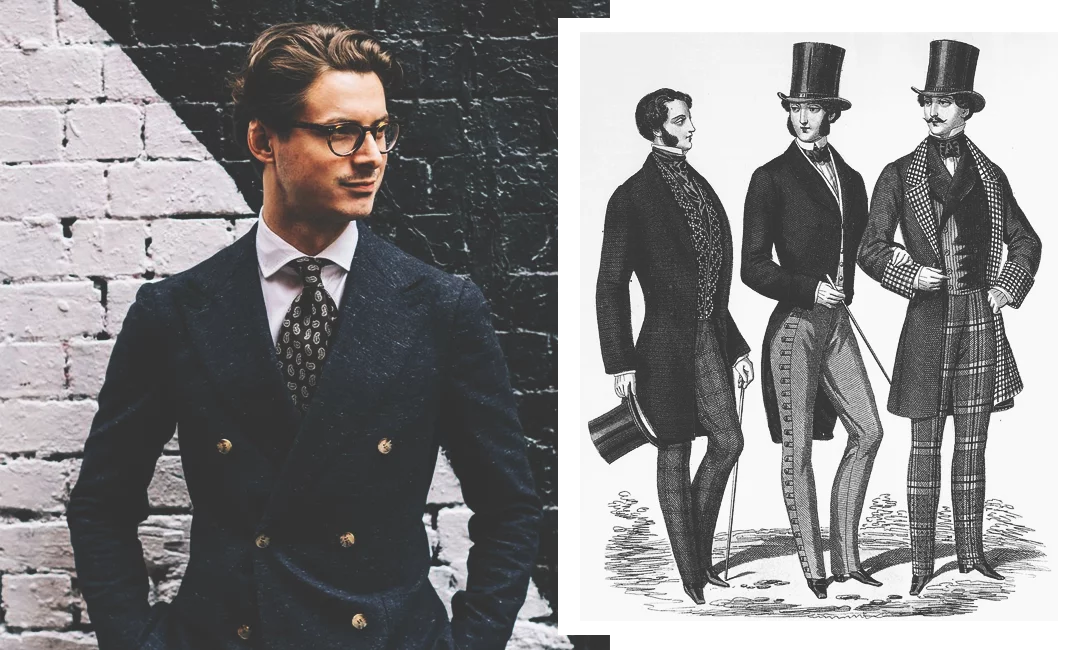

The English Club has gone down in history as a place where taciturn gentlemen in impeccable tuxedos smoke pipes melancholy or sit in leather armchairs and read the evening Times. In fact, London clubs became such only towards the end of the Victorian era, when British humor had grown to the level of the most subtle allusions and when a successful joke was sometimes reduced to one apt word. It all started with noisy revels, drunken brawls and dubious antics, which at one time were considered the height of wit.

While honest people were having fun in the fresh air, consumers of smuggled coffee created their secret dens, which became the first clubs.

When the first club appeared, the British themselves do not know. There is a legend that the first club was founded at the very beginning of the 17th century by the favorite of Elizabeth I – the famous navigator, poet and politician Sir Walter Raleigh. It is believed that among other celebrities, William Shakespeare was also a member of the club.

However, to prove that this club really ever existed is as difficult as to draw a reliable image of the historical Shakespeare. One way or another, Londoners still claim that the Raleigh club was based in the Mermaid tavern, which is quite consistent with the spirit of the first English clubs, which, having neither their own premises nor their own cash desk, moved from one tavern to another.

But the first such meeting, which definitely existed, arose precisely thanks to a joke. In 1615, the playwright Ben Jonson came up with a set of buffoonish rules for his literary bohemia friends, which the company began to follow. The rules parodied the biblical commandments, and the first sounded like this: “Let no one read bad poetry.”

The beginning of the movement of clubs

A great club movement in England was also started by people who were very inclined to humor, namely the students of Oxford University, and the law prohibiting the consumption of coffee was the main object of their ridicule. The forbidden fruit was sweet, and lovers of the smuggled potion began to secretly gather to taste the illegal drink. Most of all, an Oxford student named Creton tried to play a trick on the authorities, who not only gathered around him a circle of connoisseurs of an overseas drink, but also tried to grow coffee in his garden.

Creton was expelled from the university, but his friends did not reconcile themselves and soon began to gather at the merchant Tilyard, who knew the smugglers. The secret coffee fraternity began to call itself a club (from the word club – “club”), as if emphasizing that its members are tightly knit into a single coffee team. The word took root among coffee lovers, and later, when coffee became an indispensable attribute of English life, coffee house regulars continued to call their feasts clubs, and themselves clubmen.

Even though coffee was legalized, there was still much to laugh about in the kingdom, and coffeehouse patrons chose the government as the object of their ridicule. In 1675, King Charles II even attempted to ban coffee houses because they “invent false, malicious and scandalous gossip and then spread to the reproach of his Majesty’s government, which violates the peace and tranquility of the kingdom.”

The coffee houses temporarily disappeared, but the clubs didn’t go anywhere as the clubmen switched from coffee to ale. In the same year, 1675, the Green Ribbon Club began to meet in the London tavern “King’s Head”, whose members always wore something green on their hats. However, it was not so much a club as the electoral headquarters of the Whig party, whose relationship with the crown at that time was very difficult.

Within the walls of the tavern, clubmen wrote proclamations, drafted laws, recruited new supporters of their party, not forgetting to drink and play cards. There were some jokes too. For example, once members of the club staged a theatrical burning of an effigy of the Pope.

The Green Ribbon Club ceased to exist when some of its members lost their heads on the chopping block for anti-State activities, but the clubs in England were destined for a great future.